A brief history of how colonialism shaped the coffee trade in the 18th century.

BY J. MARIE CARLAN

BARISTA MAGAZINE ONLINE

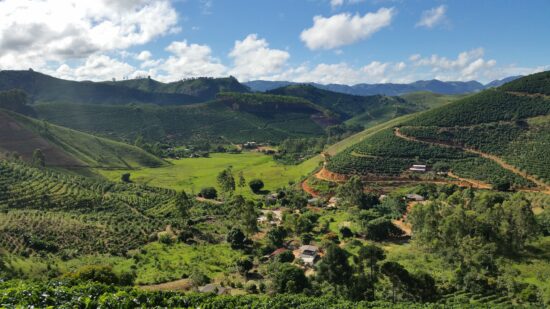

Featured image by Jeremy Stewardson via Unsplash

Coffee has traditionally been an egalitarian beverage. Known to be a leveler of class, religion, and gender, coffee is part of a societal ritual that includes everyone old enough to drink it. (Indeed, in some cultures, even children have been invited to enjoy a little “coffee milk.”) The rise of the coffeehouse has fomented revolutions, slashed economic barriers, and produced a huge international trade.

We in the industry know some of the darker sides of coffee’s history; plantations, human rights abuses, and acts of violence have been a part of many trades in the modern-to-postmodern world. Today fair and direct trade have become commonplace, as well as nonprofit groups and local governments working to protect the coffee producer. Specialty coffees in particular are often grown on small family farm lots, where the money can go directly back to the producer. Yet this was not historically the case, as coffee journeyed from one country, one continent, to another, and then another, and so on. The rise from curiosity to culture to commodity meant only one thing: Exploitation was inevitable.

The Inky Brew

Today we’ll be looking at the 18th century. It’s a big one for modernism and industrialization; it’s also when colonialism was ripening. Coffee started as a curiosity among the well-traveled of Europe, who wrote about the “inky brew“ drunk by the Turks in the 17th century. However, over time the drink became more accessible, and coffeehouses popped up all over Europe. The international coffee trade took off around 1750, and the Dutch and French were the first European empires to take advantage of the recent coffee obsession in their lands.

The Ottoman Empire jealously guarded coffee production in Yemen, which they had occupied in 1536. The rule was that no fertile coffee berries could be exported from their port in Mocha; berries were partially roasted or boiled to prevent importers from cultivating the coffee themselves. This worked until a Muslim pilgrim named Baba Budan smuggled seven seeds out and began coffee production in South India. The Dutch managed to smuggle a few trees from the Yemeni city of Aden to Holland in 1616; they were growing coffee in Ceylon by 1658. The Dutch dominated the international shipping trade, and by 1699 they had cultivated trees all over the East Indies.

By the time coffee really caught on in Europe, the ports in Java and Mocha were synonymous with coffee (we still use these terms today, although the meaning has shifted). There were more than 2,000 coffeehouses in London alone by 1700. In 1714, the Dutch gave a coffee plant to the French. A naval officer by the name of Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu snagged a plant from Paris and carried it over a transatlantic sea voyage to the French colony of Martinique, sharing his water ration with the plant.

The Rise of French Colonial Coffee

By 1750, coffee trees were growing on five continents. This enormous boom meant more workers were needed to care for and harvest the plants. Where else would such a labor force come from, if not from slavery? As Mark Pendergrast writes in his seminal coffee history book Uncommon Grounds, “Captain de Clieu may have loved his coffee tree, but he did not personally harvest the millions of its progeny. Slaves from Africa did.”

When French colonists first began growing coffee in San Domingo (Haiti), they already had a sizable population of slaves on hand for their sugar plantations. Around 1755, 80% of the coffee consumed by Europeans was West Indian. By 1788, half of the world’s coffee supply (half!) was supplied by the slave plantations in San Domingo. The workers lived in unsanitary conditions, in windowless huts, and were frequently tortured, overworked, and malnourished. A former slave later described the brutal punishments of French masters: drowning in sacks, burying alive, crushing, or crucifying slaves.

Haiti staged the only successful slave revolt in world history, a 12-year-long struggle that began in 1791. The revolutionaries burned down whole plantations and killed their owners. It’s no wonder that Haitian coffee exports dropped considerably after this. The new Haitian government, led by Toussaint Louverture, attempted to increase coffee exports again for the fledgling nation, using a system similar to medieval serfdom called fermage. Napoleon decided to invade Haiti and reclaim it for the French in 1801. He was cursing coffee and colonies by the time he gave up in 1803.

The Dutch Colonies

The Dutch were happy to pick up the slack from Haiti’s dwindled supply with their own beans from Java. In the early 1800s, a former Dutch civil servant named Eduard Dekker who had served in Java quit and wrote a novel in condemnation of the plantation system. Dekker described a famine in the fertile land, as the Dutch landowners called away workers from their own fields to harvest coffee without pay: “He withheld the wage from the worker, and fed himself on the food of the poor. He grew rich from the poverty of others.”

By the early 19th century, coffee plantations were up and running in new locales such as Brazil. Coffee demand was ever-increasing as the Industrial Revolution took off, and prices sky-rocketed, only to plummet again as Brazil harvests matured and entered the market. The threat of war between France and Spain caused a buyer’s rush, as they assumed trade routes would be cut off. Instead of war, coffee poured in not only from Brazil, but Mexico, Jamaica, and the Antilles. Prices plummeted; businesses failed all over Europe. The introduction of Latin American coffee to the world market was the harbinger of modernity for the coffee trade.

We’ll continue this look into coffee’s history in the near future.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

J. Marie Carlan (she/they) is the online editor for Barista Magazine. She’s been a barista for over a decade and writing since she was old enough to hold a pencil. When she’s not behind the espresso bar or toiling over content, you can find her perusing record stores, collecting bric-a-brac, writing poetry, and trying to keep the plants alive in her Denver apartment. She occasionally updates her blog.