We continue to explore global coffee drinks: Today we discuss café Touba, a drink that originated in Senegal and is enjoyed throughout West Africa.

BY SANDRA ELISA LOOFBOUROW

SPECIAL TO BARISTA MAGAZINE

Photos by Evan Gilman

In many places, coffee is a culinary newcomer, part of a relatively recent and still present colonial history. Whether it’s because of blossoming production and global trade, or because of the physical effects that a cup of coffee can impart, nearly every culture has developed its own particular coffee tradition. In places with strong pre-colonial culinary traditions, coffee was absorbed and adapted into existing practices, adding to the cultural miscegenation that colonialism always creates. Food and beverage traditions in particular, being intensely personal, have a way of absorbing new practices and making them their own. As an industry that prides itself on its global community and an adventurous palate, specialty coffee has a great opportunity to learn from varied and tasty traditions of coffee consumption.

In this series, I will explore regional and cultural coffee beverages and the particular confluence of historical and social circumstances that brought these beverages into existence. We’ve explored the history of café de olla and its importance and revival in Mesoamerica, and now we’ll jump into café Touba.

Café Touba

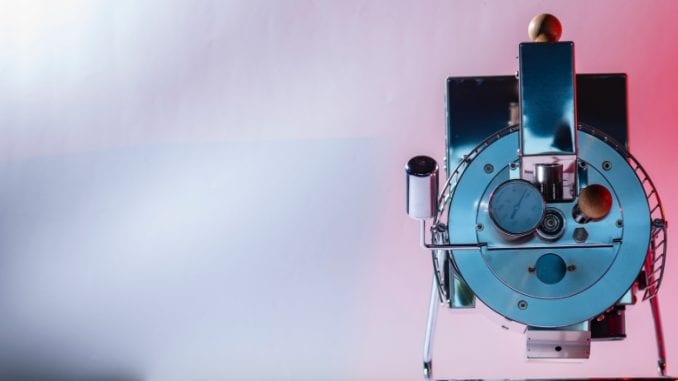

Named after the holy city of Touba in Senegal, café Touba can be found served out of mobile carts throughout the West African country. It’s made with Selim pepper (also known as grains of Selim or Guinea pepper), a spice that is not native to Senegal but which is imported in large quantities from the Gulf of Guinea, mostly from Gabon and Côte D’Ivoire. Traditionally, the Selim pepper is thrown in toward the end of the coffee-roasting process to toast up with the coffee beans, but the same effect can be achieved by toasting the grains in a pan on the stove. It is usually brewed as an infusion in large batches that can be sold, one small paper cup at a time, from the carts that either wander the streets or wait at busy intersections. It’s become such a staple in Senegal that I found multiple news articles describing how café Touba was overtaking national consumption of Nescafé—a significant feat.

The Man Behind the Beverage: Serigne Touba

Café Touba was brought to Senegal in the early 20th century by Sheikh Amadou Bamba, a Sufi religious leader. Born in 1853, Sheikh Bamba founded the Mouride brotherhood, a sect of Sufism that many Senegalese still practice today. He also established the city of Touba, now the second most populous city in Senegal, and is affectionately called Serigne Touba. He was vehemently opposed to French colonial rule, and was especially concerned with the Catholic evangelism the French were spreading through West Africa.

Serigne Touba vehemently opposed the tactics of colonization; beyond just exploiting Senegal for its natural resources, the French intended to “civilize” the Senegalese. This included converting everyone to Catholicism and making the culture conform to European ideals. Serigne Touba knew that if the French left Senegal the land might eventually recover, but the social effects of colonization would persist long after the invaders left. If the Senegalese were robbed of their cultural identity, he feared that the people would continue to participate willingly in their subjugation, and would “rush to bring [the Europeans] our wealth on a silver platter.” He strove to awaken Africans to the inferiority complex that was being forced on them, and to preserve native African (especially Muslim) traditions. He was an early participant in Pan-Africanism, an intellectual movement that sought to unify and empower both continental Africans and victims of the diaspora; he believed that Islam could be an important tool for African liberation.

Serigne Touba was a profound pacifist, but he encouraged his followers to participate in what he called “anti-colonial disobedience.” He had such a devout following that he could have easily roused a military force against the French if that had been his wish. Instead, his non-violent resistance relied, in his words, on science and piety, with the Quran and the Hadiths as his weapons. His firm but peaceful resistance made him a powerful symbol for the people of Senegal; to this day, Serigne Bamba’s image is displayed everywhere—on murals, in restaurants, or framed in peoples homes. He gathered far too much support for the comfort of the French, and so was sentenced to a long exile first in Gabon and later in Mauritania. Although the French eventually relented and allowed him to return to Senegal, Bamba remained under surveillance for the remainder of his life.

It was in Gabon that he first encountered grains of Selim. Xylopia aethiopica (known as djar in Wolof, one of the native languages of Senegal) is native to the coast of Guinea and is used in traditional medicine there. In his book Discussions of the Master of Tuubaa, Serigne Touba’s grandson Serigne El Hadji Falilou MBacké says that Serigne noticed that the French drank coffee all day, and that it seemed to give them abounding energy. Asking why they drank the bitter brew, the French told him that among other things, it improved the quality of their work. The sanctity of work is one of the central pillars of Mouridism, so Serigne Touba responded: “If you [the French], who care only about this base world, drink coffee to awaken yourselves with the goal of improving your work, then we, who wish to succeed in both worlds, should take even more advantage of this coffee than you.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sandra Elisa Loofbourow is the Tasting Room Director at The Crown: Royal Coffee Lab & Tasting Room. Her experience as a Spanish/English interpreter, working in kitchens, and teaching Argentine tango all influence and inform her approach to coffee. Sandra has been a barista, roaster, and green buyer for several companies in the Bay Area. She’s a certified Q Grader, and at Royal she does brew experimentation, coffee analysis, and creates inventive drinks. She’ll be heading up the Tasting Room at the Crown in Uptown Oakland, serving fascinating coffees and delicious education to consumers and professionals alike.