Our series on coffee-processing methods continues with a look at the honey process.

BY TANYA NANETTI

SENIOR ONLINE CONTRIBUTOR

Photos by Kenneth R. Olson

Next to the two fundamental methods of processing coffee, natural and washed, stands a third processing method common in Costa Rica and other Central American countries, which combines some of the best (and worst) aspects of the two methods: the honey process.

The first thing to note: The honey process has nothing to do with actual honey.

How It Works

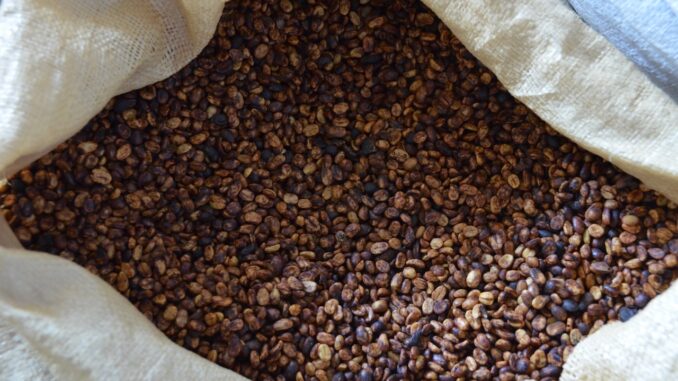

As with washed coffees, within 24 hours of the harvest with the honey process, the coffee cherries pass through a depulper to separate the coffee beans from the outer skin. The resulting beans are not completely clean, but are covered by a sticky, sugary layer of mucilage. The percentage of mucilage that remains on the beans can be specifically controlled by the action of the depulper.

This layer of mucilage, which in washed coffee is usually completely removed during fermentation, instead remains here in contact with the beans during the entire fermentation. The fermentation process usually lasts one to three days. Then, during the drying processes the honey process follows the natural method, and the mucilage dries on the exterior of the coffee bean. This remaining mucilage layer gives the coffee a sweet and almost honey-flavored taste, hence the name of the process.

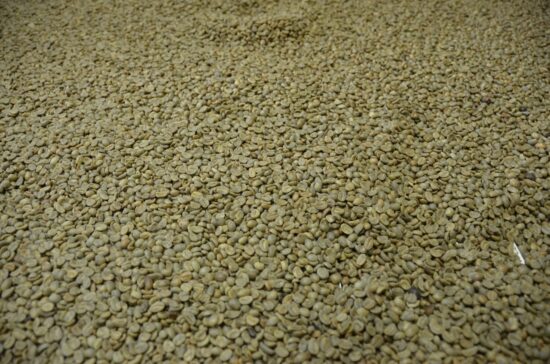

Once the beans are fully and thoroughly dried, a dry mill finishes the processing by removing any remaining fruit and mucilage from the coffee.

Multiple Types of Honey Process

But there’s more: The honey process is actually not just a single process, but a series of processing methods that all start out the same, but then differ along the way. This is where things get a little complicated, due to confusion in the naming process.

White, yellow, red, and black are all different types of honey process, but the way the names are applied is not consistent across all growing regions. A few regions still determine the honey name by determining how much mucilage is left on the beans after depulping, where the more mucilage means a darker color and name. Meanwhile, most countries adopt a different method in which the honey process name is determined by the caramelization of the sugars present in the mucilage.

While the coffee ferments, the sugars caramelize. The longer the caramelization takes, the darker the color of the mucilage, but the lower the amount of remaining sugar. So, the least fermented coffee (and therefore the most caramelized) is defined as white honey, while the most caramelized is black honey.

Confusing, isn’t it?

These different grades of mucilage left on the seed during drying give a fairly different range of flavors to honey-processed coffees, with profiles ranging from the almost washed flavor of white honey to the deeply fruity flavor of the sweet black honey.

The Results

Generally speaking, honey-processed coffees produce a truly unique result in the cup that maintains the crispness and brightness of a washed coffee, while sharing the more complex flavor profiles of a natural coffee.

They tend to have the heavier body and the sweetness of natural coffees, alongside a good clarity and a medium-high acidity typical of washed coffees. As for flavors, it is not uncommon to find notes of tropical fruits, with a fermented and complex finish.

The pros and cons of the process lie somewhere between the benefits and drawbacks of the natural and washed processes. The honey process is somewhat less ecologically demanding than washed coffee because, like natural processing, honey processing doesn’t use as much water. However, the honey process requires a long drying time and consequently a skilled labor force to ensure good results, which increases risk and cost for the producer.

At the same time, as happens in natural coffees, due to the prolonged drying times, honey-processed coffees are at higher risk of producing defects or mold, which can in turn lend to a greater risk of wasting coffee and decreasing the producer’s income.

The unique flavors and cup profiles produced by the honey process, though, can also fetch high prices for farmers when done well.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tanya Nanetti (she/her) is a specialty-coffee barista, a traveler, and a dreamer. When she’s not behind the coffee machine (or visiting some hidden corner of the world), she’s busy writing for Coffee Insurrection, a website about specialty coffee that she’s creating along with her boyfriend.